Mode of expression: Caricature

Publication: single-page image in a magazine (La Caricature), lithograph

Region: France

Relevant dates: December 1831 (publication); February 1832 (trial)

Outcome: six months imprisonment (suspended sentence); fine 500 francs

Judicial body: Tribunal de Première Instance de la Seine (civil and criminal court)

Type of law: Lèse-majesté

Themes: Defamation, Reputation, Satire, Libel

Context

Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) was the most important caricaturist in mid-nineteenth-century France, active from the Revolution of 1830 through to the fall of the Second Napoleonic Empire in 1870. A sharp-witted political and social critic, Daumier began publishing some of his earliest caricatures in La Silhouette (1829–1831), one of several illustrated satirical journals that emerged following the Revolution of 1830. Although the Revolution had promised press freedom, the editors of La Silhouette were nonetheless prosecuted and jailed during the journal’s brief existence.

Soon after, Daumier joined the staff of La Caricature (1830–1843), arguably the most prominent illustrated satirical journal of the era. Founded and edited by Gabriel Aubert and Charles Philipon—himself a talented caricaturist—the journal was seized by the authorities no fewer than thirty times and was subject to at least ten prosecutions between 1830 and 1835. One of Philipon’s most provocative images, La Poire (1831)—a visual pun in which King Louis-Philippe was depicted as a pear, a French slang term also connoting “fathead” or “simpleton”—appeared in La Caricature and left a strong impression on Daumier. Philipon’s activism earned him his own legal battle with the monarchy, the so-called guerre de Philipon contre Philippe, which ended in a six-month prison sentence and a 2,000-franc fine.

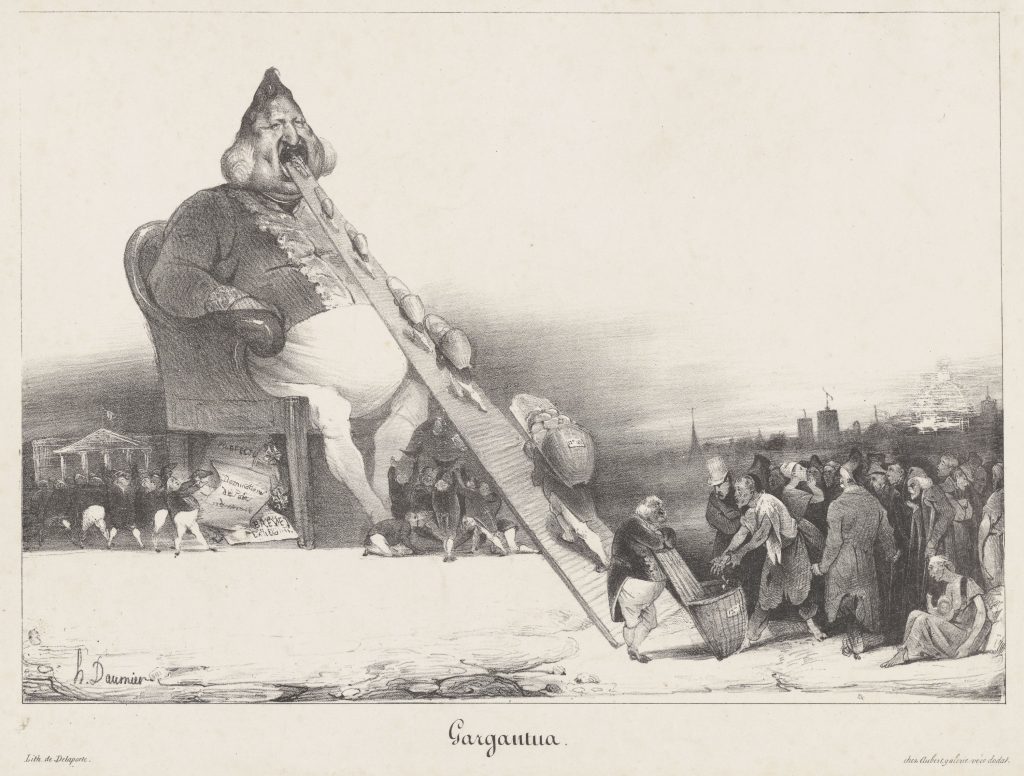

Inspired by La Poire, Daumier produced one of his most enduring and scathing works: Gargantua, published in La Caricature in December 1831. The caricature drew on François Rabelais’s satirical classic Gargantua and Pantagruel (ca. 1532–64), which had been condemned by the Sorbonne in 1533. In Daumier’s rendition, King Louis-Philippe is imagined as one of Rabelais’s grotesque giants, seated on a throne and sporting a distinctly pear-shaped head. A valet collects money from a mass of destitute working-class figures, while other valets ascend the ramp, dumping the funds into the king’s mouth. Below, one group of ministers collects the coins that have fallen, while another group of nobles, to the left, gathers the patents and rewards that the king has seemingly defecated out, before scampering off to the National Assembly. A pungent attack on pay-for-play politics, the image lay bare the trickle-up economics of a perverted revolution.

Legal Case

The publication of Gargantua quickly drew the attention of the authorities. The caricature circulated widely, both through La Caricature and in shop windows throughout Paris. In response, officials seized the print, destroyed the lithographic stone used to reproduce it, and charged Daumier with lèse-majesté, a serious offense denoting defamation of the monarch or the state. Daumier’s trial took place in February 1832. Though sentenced to six months in prison and fined 500 francs, the punishment was suspended, and he was allowed to continue his work under increasingly close scrutiny.

Yet Daumier’s troubles were far from over. Just six months after his first trial, he published La Cour du Roi Pétaud, another provocative image. This time, the authorities acted swiftly: Daumier was arrested and served a full six-month prison sentence. Far from deterring him, the imprisonment brought Daumier greater notoriety and helped to solidify his reputation. Over the course of his career, approximately two dozen of his lithographs would be censored.

Daumier’s early trials and the legal actions taken against him formed part of a broader governmental response to the perceived threat posed by the illustrated press. Alongside Philipon and other members of the pro-Republican press, Daumier’s work contributed to mounting pressure on the state to crack down more forcefully on dissent. This culminated in the passage of the so-called “September Laws” in 1835, enacted by the July Monarchy. The third of these laws introduced stricter censorship measures and imposed heavier fines and longer prison terms on publications critical of the king or the state. These censorship policies would remain in place until their repeal in 1881.

Analysis

The consequences of Daumier’s early legal troubles were far-reaching. His distinct visual style—marked by layered intertextual references and refined caricaturistic techniques—not only influenced his contemporaries but also shaped the future of political cartooning well into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. At the same time, his clashes with the authorities revealed key flaws in the government’s press policies. Most notably, post-publication prosecution frequently backfired, drawing even more attention to the very images the government wished to suppress.

The state’s fear of caricature stemmed in part from its visual immediacy. While newspapers might provoke dissent among educated readers, caricatures carried the power to broadcast biting political commentary to a broad, even illiterate, public. In a politically volatile France, this was no small threat. Caricature’s one-sided nature and capacity for mass legibility heightened its perceived danger.

As a result, artists like Daumier and Philipon adapted. Following the enactment of the September Laws, their satire became more veiled, shifting from direct attacks on identifiable public figures to broader critiques of society. Only later, between 1866 and 1872—when censorship laws were less stringently enforced—would Daumier return to more overtly political caricature.

In the end, Daumier’s experience underscored the paradox of state censorship: the more the government tried to suppress political caricature, the more it elevated the medium’s influence and cultural significance.

Sources and further reading:

Elizabeth C. Childs. “Big Trouble: Daumier, Gargantua, and the Censorship of Political Caricature.” Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 1 (Spring, 1992), pp. 26-37.

Robert Fohr. “Gargantua.” Histoire par l’image. Accessed: 21/03/2024. URL: histoire-image.org/etudes/gargantua

Robert Justin Goldstein. “The Debate over Censorship of Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France.” Art Journal, vol. 48, no. 1 (Spring, 1989), pp. 9-15.

Robert Justin Goldstein. “Fighting French Censorship, 1815-1881.” The French Review, vol. 71, no. 5 (April, 1998), pp. 785-796.

Robert Rey, Honoré Daumier (New York: Abrams, 1985).

Judith Wechsler, “Daumier and Censorship, 1866-1872,” Yale French Studies, no. 122 (2012), pp. 53-78.