Mode of expression: Caricature

Publication: Singlesheet print, etching

Region: Great Britain

Relevant dates: 9 January 1796 (publication); late January 1796 (arrests)

Outcome: warning; prosecution abandoned

Judicial body: not applicable

Type of law: Blasphemy

Themes: Religion, Defamation, Royal Family, Satire

Context

James Gillray (1756–1815) was one of the most important and distinctive British visual satirists and printmakers of the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and was renowned for his biting political caricatures. He was trained as an engraver and briefly attended the Royal Academy, but eventually turned to visual satire, producing hundreds of prints that lampooned everything from private foibles to the British monarchy and Parliament. Gillray also frequently commented on international affairs, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars, and directly targeted the major figures of the day, including King George III and the Prince of Wales, the politicians William Pitt the Younger and Charles James Fox, and Napoleon Bonaparte, often portraying them in absurd or unflattering ways.

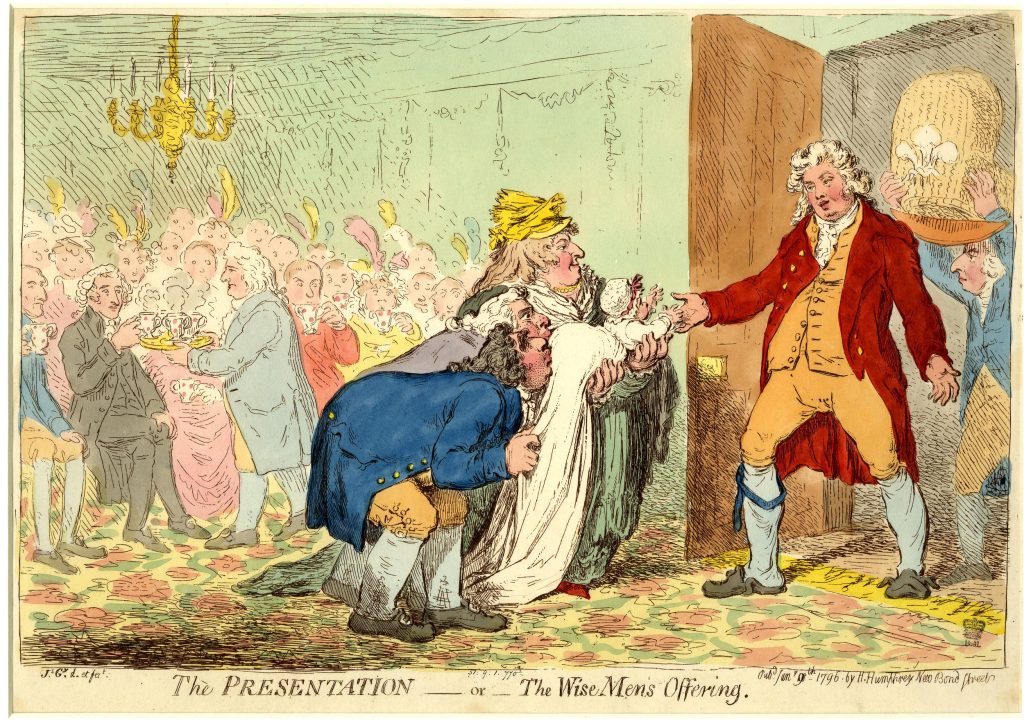

James Gillray’s The Presentation, or, Wise Men’s Offering, published on 9 January 1796, offers a scathing satire of the British royal family through a winking religious allusion, and was printed and sold by Hannah Humphrey, one of the most important printsellers of the period (Contogouris and Denis 2022). As one visitor to London remarked, shocked to discover that Humphrey was located just yards from the Royal Palace, her printshop was “a manufactory […for ] throwing off libels against” the crown (qtd. Donald, 1996, p. 2).

The Presentation’s publication coincided with two important events: the Christian feast of the Epiphany on January 6, which commemorates the presentation of the infant Christ to the Magi; and the birth of Princess Charlotte, the first and only legitimate child of George, Prince of Wales (later George IV), just a day later, on January 7.

The print depicts an imagined scene at Carlton House, the Prince of Wales’s London residence. At the centre of the image is an exaggeratedly stout woman, who holds the infant Princess Charlotte in the air. In the doorway to the right, the Prince of Wales staggers drunkenly in, with unlatched shoes and his Order of the Garter insignia dangling from his leg (“Honi soit [qui mal y pense]”: shame on him who thinks evil of it), taking his newborn child’s hand. He is trailed by Michael Angelo Taylor, the prince regent’s close friend and a member of parliament, who holds a wicker cradle adorned with the prince’s heraldic feathers.

To the infant’s left, two politicians (the “wise men”), Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, subserviently stoop to kiss Princess Charlotte’s posteriors, as Fox clutches at the infant’s long robe. Their fawning obsequiousness mocks the performative loyalty of politicians seeking royal favour. In the background, elaborately dressed partygoers presumably consume caudle, a typically alcohol-laced postpartum beverage, a bit like an eggnog or posset, recognizable by the distinctive two-handled cups. In the front row sit two other politicians, wisely waiting to offer their own obeisance to the newborn: John Montagu, 5th Earl of Sandwich, and Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine.

The precise identity of the stout woman—a problem common to satirical prints from this period, when satirists and printsellers were careful never to name their victims outright—has been subject to debate. One possibility is that the woman is Maria Fitzherbert, the Prince’s former clandestine wife, a Roman Catholic widow six years the prince’s senior, whom he had secretly married in 1785.

Gillray’s imagined take on the entire affair thus merges political and personal commentary with an irreverent parody of sacred ritual. Taken altogether, the print offers a glimpse of the gossipy background that attended many political satires from this period, offering a fictional first-person view of the political horse trading and everyday grift and sleaze of late-eighteenth-century pay-for-play politics, a familial celebration turned to vulgar spectacle of vice and opportunism.

Legal Case

The Presentation is the only known instance in Gillray’s prolific and often provocative career for which he was actually arrested. The print’s release prompted an almost immediate legal response, leading to a series of arrests and a short-lived but notable inquiry into the work’s sellers for blasphemy.

According to the Evening Mail of 22 January 1796:

On Saturday morning James Gillray, a Caricature Print-engraver, was brought before the sitting Magistrate; at the Public-office, Bow-street, charged with selling a certain burlesque Caricature Print, entitled “The Wise Man’s Offering,” which is a burlesque on the presenting [of] the infant Princess to the Prince of Wales, and several well-known characters are introduced. He was admitted to bail.

This brief but suggestive report makes clear that the Crown was going after Gillray not for seditious libel—a loosely defined branch of defamation law that the authorities had turned to throughout the eighteenth century to manage the press (Hamburger, 1985)—religious offence. What triggered the arrest was not the caricatured depiction of the Prince of Wales (a frequent subject of ridicule) or the exposure of Whig hypocrisy, but rather the appropriation and mocking distortion of the sacred Christian narrative of the Epiphany.

Interestingly, the crackdown did not stop with Gillray. A day before his detainment, the London Daily Advertiser reporter (25 January 1796), two print sellers—Samuel William Fores and James Aitken—were also arrested for selling copies of the print. Curiously absent from the arrests was Humphrey. It is impossible to know, however, whether the selective enforcement in the arrests signals careful calculation or simply inconsistency in the handling of the case. Despite the initial arrests and the attention in the newspapers, the charges never progressed (Hill, 1965, pp. 61-62).

Analysis

Despite the abandoned prosecution, the legal attention around The Presentation marks another key moment in the evolution of legal approaches to visual satire in the eighteenth century. As a scathing hybrid of political commentary and religious parody, Gillray’s print offered a jarring collision of sacred and profane. As always, the Prince was depicted as the drunken embodiment of royal vice. The print’s politicians hardly got off better. Fox and Sheridan, the two “wise men,” are reduced to obsequious court jesters, smooching a baby’s backside in a literal act of knee-bending political sycophancy, offering a grotesque parody of the Epiphany, with no gold, frankincense, or myrrh to offer, but only their own debased flattery and self-interest.

In linking this moment of political servility to a moment of national celebration, the print’s blasphemy raises questions about the ritualistic aspects of political corruption. At the centre of the image is thus Princess Charlotte, an infantile messiah, worshipped by drunkards and flatterers, in a procession that directly inverts the solemnity of the biblical nativity. Gillray’s print therefore poses a deeply subversive question: If this is the future of the British monarchy, what kind of saviour—or damnation—does she represent?

The Presentation also marks a transition in the Crown’s efforts to regulate the burgeoning and ever-expanding marketplace for visual satire in the later eighteenth century. The courts still a nonstarter, the Prince of Wales, as both Prince Regent and later King George IV, began to produce his own propaganda, countering his many visual critics in the press. He also often purchased the most offensive prints, hoping to remove them from circulation. In one print from 1819, for instance, a tipsy Prince of Wales, comically riding a female cook, declares with drunken pride, “If the rascals caricature me, I’ll buy em All up d—me.” So extensive were his efforts that by the time of his death, in 1830, the royal collection had swelled to a staggering 2,750 caricatures (Heard, 2016, p. 146). In the end, George IV simply resorted to bribery on a massive scale (Wardroper, 1973, p. 213.) Between 1819 and 1822, the king paid out some £2,600 to print sellers and artists to suppress individual works. George Cruikshank, for instance, signed a receipt for £100 pounds, promising “not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation” (qtd. George, 1959, p. 188). These payouts also seemingly worked: many of the largest print sellers and the most prominent caricaturists slowly turned away from anti-monarchical satire (Gatrell, 2007, pp. 536-40).

Sources and further reading:

Contogouris, Ersy and Denis, Béatrice. “Hannah Humphrey, London’s Leading Caricature Printseller.” ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830: 12.2 (2022), Article 1.

http://doi.org/10.5038/2157-7129.12.2.1259

Donald, Diana. Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Gatrell, Vic. City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London. New York: Walker & Co., 2007.

George, M. Dorothy. English Political Caricature, 1793-1832: A Study of Opinion and Propaganda. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959.

Hamburger, Philip, “The Development of the Law of Seditious Libel and the Control of the Press.” Stanford Law Review 37.3 (February 1985): pp. 661–765.

Heard, Kate. “The British Royal Family and Satirical Prints, 1760-1901.” In Collecting Prints and Drawings. Ed. Andrea M. Gáldy. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Hill, Draper. Mr. Gillray, the Caricaturist. London: Phaidon, 1965.

Wardroper, John. Kings, Lords and Wicked Libellers: Satire and Protest, 1760-1837. London: John Murray, 1973.