Mode of expression: Parody advertisement

Publication: Pornographic magazine

Region: United States

Relevant dates: November 1983 (publication); February 1988 (Supreme Court ruling)

Outcome: Hustler magazine acquitted

Judicial body: Supreme Court of the United States

Type of law: Civil Law, Constitutional Law

Themes: Defamation / Reputation / Infliction of Emotional Distress / Satire

Context

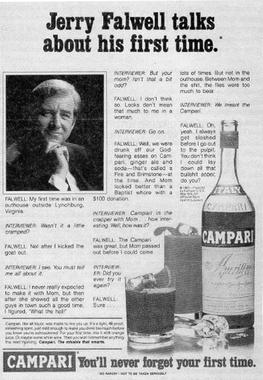

Hustler v. Falwell (485 U.S. 46, 24 February 1988) is one of the most influential satire-related decisions in U.S. jurisprudence. In November 1983, the pornographic magazine Hustler – founded by American entrepreneur Larry Flynt – featured on its front cover a parody of a famous Campari advertisement campaign, where various celebrities were interviewed about their first time trying the drink. Hustler’s spoof of the advertisement instead displayed the name and picture of Reverend Jerry Falwell, a high-profile televangelist and political commentator, adding the title: “Jerry Falwell talks about his first time,” with his “first time” taking on a much more explicit sexual meaning. In the fake interview, Falwell confesses that his “first time” was during a drunken, incestuous relationship with his mother. The small print at the bottom of the page features the disclaimer “Ad parody—not to be taken seriously.” The magazine’s table of contents also listed the ad as “Fiction; Ad and Personality Parody.”

Legal case

Falwell brought a lawsuit against Hustler and its publisher on three different grounds: invasion of privacy, defamation, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. The judge ruled against Falwell with regard to invasion of privacy and defamation, stating that the parody ad could not “reasonably be understood as describing actual facts about [Falwell] or actual events in which he participated.” However, the court ruled in Falwell’s favor on the emotional distress claim, stating that he should be awarded $100,000 in compensatory damages and $50,000 in punitive damages from each defendant. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld the judgment in its entirety, reiterating that the defendants had acted intentionally and recklessly in inflicting emotional distress.

Following an appeal from Hustler’s publisher, the Supreme Court reversed the previous rulings. According to the Court, the First and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit a public figure from recovering damages for intentional infliction of emotional distress, without showing in addition that the publication contains a false statement of fact made with actual malice (i.e., one that is made while being aware of the falsity of the statement, or displaying reckless disregard for whether a statement is true). In its opinion, the Court referred to the long history of political satire in the U.S., and to its vital role in democratic debate:

Despite their sometimes caustic nature, from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate. […] From the viewpoint of history, it is clear that our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them. (at 53-55)

The Court acknowledged that “the caricature of respondent and his mother published in Hustler is at best a distant cousin of the political cartoons described above, and a rather poor relation at that.” Nevertheless, it rejected Falwell’s claim that the parody ad was so “outrageous” that it deserved a harsher treatment than a traditional political cartoon. In the Court’s view, adopting “outrageousness” as a standard for curtailing expression has “an inherent subjectiveness about it which would allow a jury to impose liability on the basis of the jurors’ tastes or views, or perhaps on the basis of their dislike of a particular expression.” As a consequence, the perceived outrageousness of a given expression “cannot, consistently with the First Amendment, form a basis for the award of damages for conduct such as that involved here.”

Analysis

By stressing that Hustler’s parody in the case could not reasonably be interpreted as asserting “actual facts” about Falwell, the Court relied on what humor scholars would call incongruity – namely some kind of implausible deviation from everyday logic or (culturally constructed) standards, norms and expectations. Within a judicial context, incongruity is often seen as a key indicator of humorous intent, preventing the audience from interpreting a given expression as (for example) a factual defamatory statement.

In the specific case of the Campari ad, incongruity is achieved by means of satirical reversal. In other words, a notoriously conservative and prudish public figure is associated with obscene sexual content, which creates a stark contrast between the Reverend’s worldview and his (fictional) conduct. This ‘world-upside-down’ logic is typical of political satire across different cultures, and is a central feature of what Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin described as the “Carnivalesque.” In Bakhtin’s definition, since classical antiquity, the Carnivalesque is characterized by: 1) An emphasis on the human body, especially in its ‘lower’ functions (ingestion, sexuality, evacuation); 2) A merging or juxtaposition of opposites (the high and the low, the sacred and the profane, etc.); and 3) A temporary reversal of political and moral hierarchies by means of blasphemy or obscenity, unveiling the “relativity of all structure and order” (Bakhtin 1984: 122–125). Through the lens of the Carnivalesque, Hustler’s parody can be reconsidered as a modern descendant of a centuries-long satirical tradition, where representatives of the political or religious establishment are reduced to vehicles of elementary bodily functions. Another controversial example of ‘carnivalesque satire’ is the painting at the center of Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria (also featured in this catalogue).

The Hustler v. Falwell case also features prominently in The People vs. Larry Flynt, a 1996 film directed by Miloš Forman starring Woody Harrelson as Flynt, Edward Norton as Flynt’s lawyer Alan Isaacman, and Burt Neuborne (a civil rights attorney who had contributed to Flynt’s defense) as Jerry Falwell’s lawyer. Later in the 1990s, Falwell and Flynt started meeting in person and engaged in public debate on morality and the First Amendment. As stated by Flynt following the Reverend’s death in 2007: “the ultimate result was one I never expected … We became friends” (‘The porn king and the preacher,’ Los Angeles Times, 20 May 2007).

Sources and further reading:

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1984. Rabelais and his world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Little, Laura. 2019. Guilty pleasures: Comedy and law in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.