Mode of expression: Comic book

Publication: Calendar

Region: Europe (Belgium)

Relevant dates:

Date of publication: January 9, 2011

Date of Final outcome: September 3, 2014

Outcome: Recommended for Decision in Accordance with Ruling

Judicial body: Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)

Type of law: Civil Law, International/Regional Human Rights Law

Themes: Artistic Expression, Discrimination, Parody, Copyright

Context

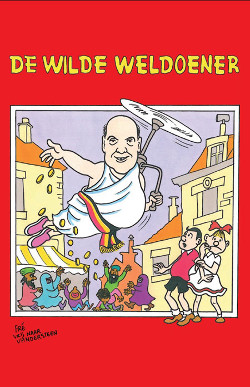

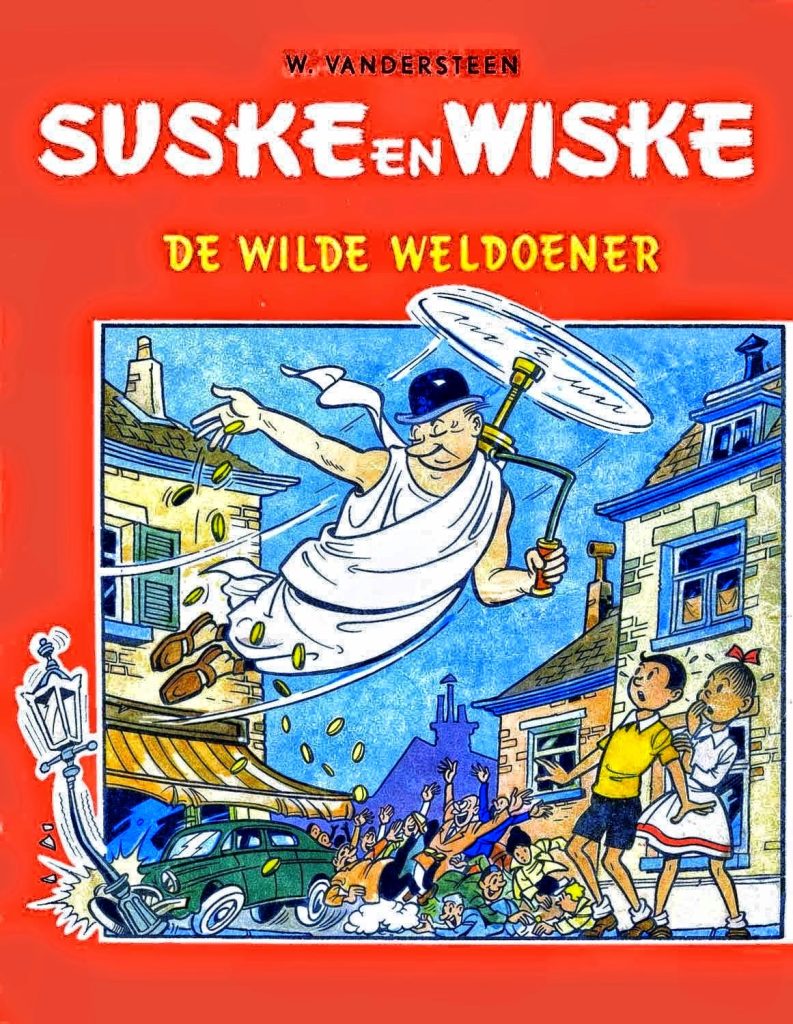

New year, new plans and resolutions. Making this tangible, Deckmyn, a member of the political party Vlaams Belang, handed out a calendar at a New Year’s reception of the city of Ghent on 9 January 2011. The front page featured an adaptation of a cover of the Suske and Wiske comic book De Wilde Weldoener (i.e., ‘The Wild Benefactor’) by Willy Vandersteen. The main character was replaced with an image suggesting to be the mayor of Ghent, while figures picking up the coins that the main character threw around were substituted with people of color and persons wearing headscarves.

Legal Case

Heirs of Vandersteen filed a complaint of copyright infringement, arguing that that the drawing on the front page of the calendar and the communication to the public constituted an infringement of their rights. The court of first instance of Brussels indeed ordered that the defendants – including also the Vrijheidsfonds – stop the spread of the calendar, whereas a failure to do so would lead to a periodic penalty.

Before the court of appeal, the defendants argued that the drawing in this case constituted a political cartoon falling under the scope of parody in Belgian copyright law, specifically Article 22(1) under (6). The heirs of Vandersteen, on the other hand, argued that a parody has to meet certain conditions, which would not be the case here. Also, they held that the drawing conveyed a discriminatory message.

This led the court of appeal of Brussels to ask a number of questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (hereafter: CJEU or the Court) for a preliminary ruling on the parody exception to copyright law, as laid down in Article 5(3)(k) of Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (OJ 2001 L 167, p. 10) (hereafter: Infosoc Directive). The questions asked by the Belgian court were:

1. Is the concept of “parody” an autonomous concept of EU law?

2. If so, must a parody satisfy the following conditions or conform to the following characteristics:

– display an original character of its own (originality);

– display that character in such a manner that the parody cannot reasonably be ascribed to the author of the original work;

– seek to be humorous or to mock, regardless of whether any criticism thereby expressed applies to the original work or to something or someone else;

– mention the source of the parodied work?

3. Must a work satisfy any other conditions or conform to other characteristics in order to be capable of being labelled as a parody?

Analysis

With this referral the concept of parody is drawn into the copyright sphere at the highest European level, being the first case in which the CJEU interprets the parody exception. Firstly, the CJEU holds that ‘parody’ is indeed an autonomous concept of European Union law, since the Directive makes no reference to national laws in this provision. This means that it must be interpreted in a uniform way throughout the EU. While this approach makes sense with the issue at stake being a legal one, it should be remembered that the concept of parody in itself is of course much older than copyright law as such. It has become legally relevant only with the introduction of the concept in rules of copyright on permissible – or not permissible – reproductions and distribution of cultural works (Koelman, 2014, p. 207; Kuitert and Klomp, 2014, p. 189).

Next, taking the second and third questions together, the Court holds that – since the Directive lacks a definition – the parody concept should be understood according to its “usual meaning in everyday language”, taking into account the context and objectives of the rules of which it forms part. Following the Advocate General’s (AG) Opinion in this case, the Court states that essential characteristics of ‘parody’ are comprised of two elements: the parody should evoke an existing work, while being noticeably different, and constitute an expression of humor or mockery. Where the AG references – not further specified – “art theory” and “literary theory” when discussing his identified structural and functional features of parody in his Opinion in the case, the Court leaves out any reference. This is understandable, as this is in line with the Court’s usual M.O. However, it is still interesting to observe that in this way the concept of parody seems to be detached from its literary origin and fully legalised as a copyright concept.

Where requiring noticeable differences makes sense from an intellectual property perspective, this deviates from literary theory viewpoints where definitions include aspects such as minimal transformation or dialogue with the original (Genette, 1997, p. 19; Sadrian, 2010, p. 87, referencing Bakhtin, 1990; Breemen & Breemen, 2022, p. 468). The general idea of the parody exception is the absence of having to request the permission of the original author to use the work. If this would be the case, it would be all too easy for disagreeing authors to reject such requests for use, hence the exception to the monopoly-style right. Questions that do remain are: where does the parody become a derivative work, and how does the parody exception relate to authors’ moral rights? (Goldstein & Hugenholtz, 2010, p. 380) The second requirement of ‘constituting humor or mockery’ places these non-legal concepts in a legal sphere. This has resulted in commentators wondering if, when assuming that the Court means that parodies must have a ‘humorous effect’, this means that “only actually funny people” can rely on the parody exception, which would not be in line with the right to freedom of expression that Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees for everyone (Rosati, 2015, p. 518). Moreover, how can the presence humor be determined in courtrooms? Should this be done by the presiding judge or a panel of expert comedians? (Rosati, 2015, p. 518; Kuitert, 2006, p. 39) The CJEU further indicates that no other requirements, such as those mentioned by the Belgian court of appeal, have to be met. Neither does the parody have to concern, for example, solely the original work or display an original character of its own other than demonstrate noticeable differences.

As to the context and objectives, two things stand out. Firstly, the Court notes that parody is an appropriate way to express an opinion, in line with recital 3 of the Infosoc Directive which states that the harmonisation of the Directive relates to, amongst other fundamental principles and rights, freedom of expression. This underscores the fundamental basis for the parody exception. What has sparked much debate, then, is the Court’s observation with regard to another recital of the Directive — namely number 31, which addresses the need for a fair balance between right holders and users. On the one hand, this is not surprising, since it is a general principle of intellectual property law to find a balance between exclusive rights and interests of users; however, the reasoning of the Court — which almost goes into a substantive judgment on the merits of the case, which should be left for the national court to decide — gave rise to legal commentary. Per the Court, in the case of a discriminatory message, right holders have a legitimate interest to not have their work associated with such a message, based on the principle of non-discrimination. Whereas it is agreed upon that parodies, like other expressions, find their limits in the fundamental principle of non-discrimination (Hugenholtz, 2016, p. 4667; Breemen & Breemen, 2022, p. 474), legal commentators caution against too readily accepting authors’ opposition against ‘unwanted associations’. This would not only limit the very freedom of expression that the Court in fact underlines, but also go against the essence and format of parodies lying in their potential offensiveness and the absence of having to ask permission of the right holder, respectively (Hugenholtz, 2016, p. 4667; Voorhoof, 2014a, p. 299). To conclude, the context of copyright showcases both the specific features of parody and the tensions this may bring in relation to the original author.

Sources and further reading:

Breemen, Kelly & Breemen, Vicky. 2022. Imagining interdisciplinary dialogue in the European Court of Justice’s Deckmyn decision: Conceptual challenges when law and technology regulate parody. Humor 35(3), Journal nummer, 447-482.

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsests, trans. Channa

Newman and Claude Doubinsky (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Goldstein, Paul & Hugenholtz, Bernt. International Copyright. Principles, Law, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Hugenholtz, Bernt. 2026. Annotatie bij Hof van Justitie EU 3 september 2014 (Deckmyn/Vandersteen). Nederlands Juristenblad 37, 4666.

Koelman, Kamiel. 2014. Annotatie bij Hof van Justitie EU 3 september 2014 (Deckmyn/Vandersteen). Tijdschrift voor Auteurs-, Media & Informatierecht 6, 207.

Kuitert, Lisa. (2006) ‘Hoe Origineel is de Literatuur?’ in Parodie. Parodie en Kunstcitaat, ed W. Grosheide (Den Haag: Boom Juridische Uitgevers), 40.

Kuitert, Lisa & Klomp, René Klomp. 2014. Ruim Baan voor de Literaire Parodie. Tijdschrift voor Auteurs-, Media & Informatierecht 6, 186-190.

Rosati, Eleonora. 2015. Just a Laughing Matter? Why the Decision in Deckmyn is Broader than Parody. Common Market Law Review 52, 513.

Sadrian, Mohammad R. 2010. Parody: Another Revision. Journal of Language and Translation 1, 85-90.

Voorhoof, Dirk. 2014a. Hof van Justitie rekt parodie-begrip op, maar hete aardappel komt terug op het bord van de nationale rechter. Mediaforum 11-12, 296-99.

Voorhoof, Dirk. 2014b. De parodie als geharmoniseerd EU-concept: op zoek naar een rechtvaardig evenwicht tussen auteursrecht en expressievrijheid. AMI TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR AUTEURS-, MEDIA- EN INFORMATIERECHT 6, 179–185.