Mode of expression: Press cartoons

Publication: Charlie Hebdo

Region: Europe (France)

Relevant dates: 8 February 2006 (publication); 22 March 2008 (final decision)

Outcome: Acquittal

Judicial body: Paris Court of Appeal

Type of law: Criminal Law

Themes: Incitement to hatred / religion

The “Muhammad cartoon case” has been considered “the first transnational humor scandal” (Kuipers, 2011), not only related to freedom of expression, religious tolerance, and the relationship between Islamic and Western countries, but also to humor and cartoons as specific forms of contemporary communication. The controversy arose in 2005 when the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten launched a contest among cartoonists, inviting them to draw the prophet Muhammad (which is typically prohibited by Islam). The newspaper eventually published a dozen heterogeneous cartoons depicting the prophet, in various styles and tones, in September 2005.

Context

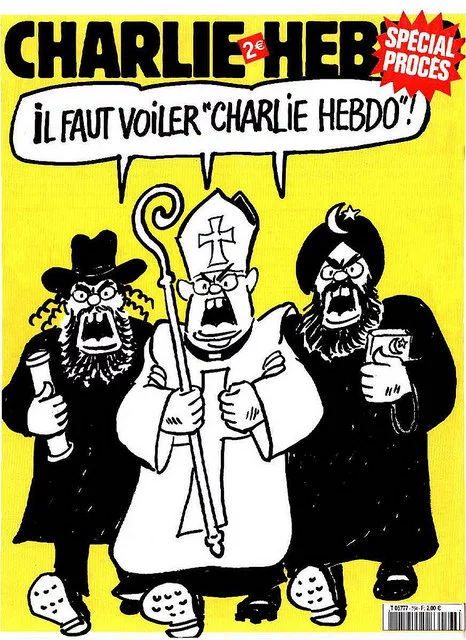

The publication of the cartoons caused diplomatic problems between the ambassadors of Muslim-majority countries whose embassies were stationed in Denmark and the Danish government, and was followed by demonstrations, boycotts of Danish products and violent protests that spread across both Muslim-majority and European countries. The Western press was divided on the decision whether to publish or not the controversial cartoons. In line with its belief that doing so signified a defense of free speech, Charlie Hebdo republished the cartoons in February 2006, in an entire issue devoted to the Muhammad cartoon affair. The cover of the edition presented a controversial cartoon of its own by Cabu. It showed a bearded man covering his face with his hands, saying: “It’s hard being loved by jerks!” (C’est dur d’être aimé par des cons!”). Next to the cartoon, a caption stated: “Muhammad overwhelmed by fundamentalists” (Mahomet débordé par les intégristes).

Legal case

The French Council of the Muslim Faith, the Grande Mosquée of Paris, and the Union of Islamic Organizations of France filed a lawsuit against Philippe Val, the editor in chief of Charlie Hebdo, for “public insult towards a group of people based on their religion.” The legal action was only taken against three cartoons: two of the twelve Danish drawings and the one by Cabu that appeared on the cover of Charlie Hebdo. One of the Danish cartoons depicted Muhammad with his head covered by a bomb-shaped turban. The other one showed the prophet in heaven, saying to terrorists: “Stop stop we ran out of virgins!” According to the Koran, those who perform certain acts of faith are promised the company of young virgin women in paradise.

The trial took place on 7 and 8 February 2007, before the 17th Correctional Chamber of the Paris High Court, which specializes in press matters. Ultimately, on 23 March 2007, Philippe Val was acquitted. In its ruling, the Paris Correctional Court argued that “France, a secular and pluralistic society, respects all beliefs while also maintaining the freedom to criticize religions of any kind and to depict subjects or objects of religious veneration; blasphemy, which offends divinity or religion, is not repressed here.” The court also ruled that “the literary genre of caricature, although deliberately provocative, participates as such in the freedom of expression and communication of thoughts and opinions,” and that the cartoons published in Charlie Hebdo “appear devoid of any deliberate intention to offend directly and gratuitously all Muslims.” The court argued that the cartoons should be interpreted in the context of the special issue, which sought to participate in the “debate of ideas on the excesses of certain proponents of fundamentalist Islam that have led to violent outbursts.” The Union of Islamic Organizations of France appealed the decision against Philippe Val, but his acquittal was upheld by the Paris Court of Appeal on 22 March 2008.

Analysis

Many of the drawings depicting the prophet Muhammad published by Jyllands-Posten were vague, playing with ambiguity and implicitness, and the sacred figure was only explicitly identified in the editorial that accompanied the publication. The newspaper’s culture editor, Flemming Rose, stated that, when commissioning the cartoons, their goal “was simply to push back self-imposed limits on expression that seemed to be closing in tighter.” In his editorial, Rose (2005) writes:

The modern, secular society is rejected by some Muslims. They claim a special position when they insist on special consideration for their own religious feelings. It is incompatible with a secular democracy and freedom of expression, where one must be ready to put up with scorn, mockery, and ridicule. It is certainly not always sympathetic and nice to look at, and it doesn’t mean that religious feelings should be ridiculed at any cost, but it is subordinate in the context.

Besides their ambiguity and implicitness, which are characteristic features of cartoons, the editorial underscores the satirical nature of cartoons, associated with derision, mockery and ridicule. A large part of the Muslim community indeed felt that the publication was mocking their religion and beliefs. Moreover, images, which are particularly polysemous, are difficult to interpret. The coexistence of multiple divergent interpretations was a recurrent among those who positioned themselves on opposing sides of the debate.

One of the cartoons that triggered the greatest debate portrays a bearded man with a lighted bomb in place of his turban. While many people interpreted this cartoon as an amalgam between Islam and terrorism, and extended it to encompass the Muslim community as a whole, Jyllands-Posten’s culture editor argued that the cartoon pointed solely to fundamentalists who commit acts of terrorism: “Some individuals have taken the religion of Islam hostage by committing terrorist acts in the name of the Prophet” (Rose, 2006). As seen above, this was also the French courts’ interpretation.

The Muhammad cartoon controversy raises important questions about “humor regimes” (Kuipers, 2011) which establish who can laugh with whom and about what. In this instance, believers and non-believers did not share the same ideas about the topics that could be addressed and published. Not only was the topic taboo but the original situation of communication was narrowly related to power dynamics that divided those who mocked and laughed (an established Danish newspaper and the Danish non-Muslim majority) and those who felt that they were being targeted (the Muslim community in Denmark).

Sadly, this controversy would be followed years later by numerous violent events that led to the death of dozens of people in Europe, notably the terrorist act perpetrated in the offices of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015.

Sources and further reading:

Kuipers, Giselinde. (2011). The politics of humour in the public sphere: Cartoons, power and modernity in the first transnational humour scandal. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(1), 63–80.

Rose, Flemming. (2005) Muhammeds Ansigt. Jyllands-Posten, 30 September.

Rose, Flemming. (2006) Why I Published Those Cartoons. Washington Post, 19 February. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/17/AR2006021702499.html