Mode of expression: Photomontage and headlines

Publication: Satirical magazine Barcelona

Region: South America (Argentina)

Relevant dates: 13 August 2010 (publication); 20 December 2020 (final outcome)

Outcome: Supreme Court overturns fine against satirical magazine

Judicial body: Argentinian Supreme Court (final appeal)

Type of law: Civil Law

Themes: Defamation / Reputation / Satire / Gender violence / Private figure / Public figure

Context

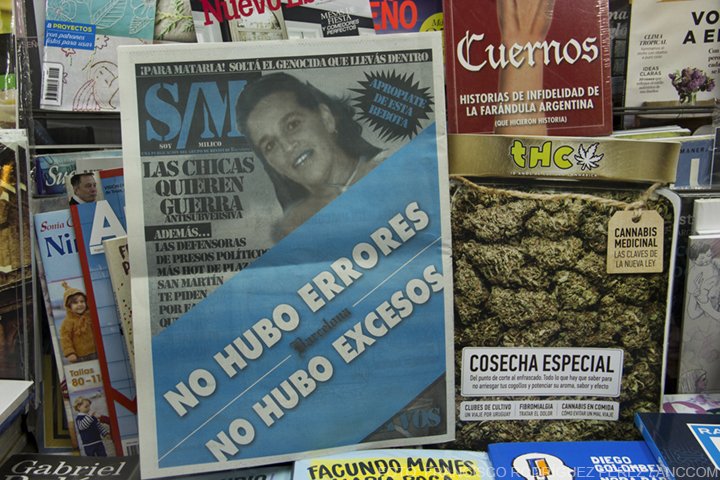

Cecilia Pando de Mercado is President of the Association of Relatives and Friends of Political Prisoners of Argentina and the wife of a military officer. She gained notoriety for her active participation in the public debate on the trials related to the violation of human rights during the last dictatorship (1976-1983). In August 2010, Pando and some wives of convicted military officers chained themselves in front of the headquarters of the Army and the Ministry of Defense asking for a meeting with the Minister of Defense. The satirical magazine Barcelona published a photomontage portraying Cecilia Pando de Mercado’s head and the body of an unknown naked woman with her hands tied together, bondage style.

The magazine sarcastically named this edition “Soy milico” (“milico” being a pejorative slang term for a military member). The cynical and provocative tone was extended across the multiple headlines that accompanied the photomontage: “Get this baby”, “Girls want anti-subversive war”, “The hottest political prisoners’ defenders of San Martín Square ask you to please release them”, “To die for! Let go of the genocide inside you”, “Chains, humiliation and coup d’état”, “Ceci Pando chains herself for you”.

Legal case

In August 2010, immediately following the publication, Pando de Mercado obtained a precautionary measure to withdraw the magazine from circulation. In 2012, she sued the magazine, arguing that the publication of “pornographic content” had violated her rights to honor, privacy and moral integrity. The first instance court held that Barcelona had injured Pando de Mercado’s honor and ordered the newspaper to pay Argentine Pesos 40000. Both parties appealed the ruling at the National Civil Court of Appeals, which confirmed the decision in 2017 and resolved to increase the sum to ARS 70,000 (equivalent to USD 4,485 at the time). Both courts differed, however, in the status attributed to Pando de Mercado: Was she a private or a public figure? The court of appeal held that her voluntary participation in the public domain had become of general interest.

In response to the ruling, Barcelona filed an extraordinary appeal before the National Supreme Court. On 22 December 2020, the Supreme Court of Justice reversed the conviction, ruling that Barcelona is a magazine of political satire, the function of the photomontage is analogous to that of caricature, Pando is a public person and no gratuitous insult or unjustified vexation were carried out by the publication. As the Court wrote, the photomontage should be considered a “satirical graphic composition through which a political criticism was exercised in an ironic, poignant, irritating and exaggerated manner” (63667/2012/CS1, 22 December 2020, p. 20). Interestingly, the judges referred to several elements of discourse analysis to frame their arguments and quoted a concept proposed by the semiotician Eliseo Verón (1992) about the tacit “reading contract” established between the newspaper and its readership. They found that, “as a graphic medium dedicated to satirical manifestations of political and social reality, no reader could believe that they were facing an authentic message, nor that the sentences that accompanied it were true. It can only be inferred from them that, with the sarcasm and exaggeration characteristic of the magazine in question, political criticism was being carried out without exceeding the constitutional protection of the right to freedom of expression and criticism” (p. 21).

In relation to the petitioner’s arguments that “she was attacked for her status as a woman”, the judges noted that

“it is not noticed that the expressions in this case constitute clear discriminatory insults that, in a way disconnected from the political criticism they entail, use the female profile as a way to reaffirm stereotypes and/or gender roles that subordinate women. The demandant concise argument in this regard does not override – and, moreover, it loses sight – that the publication reveals a clearly satirical discourse regarding the behaviors that motivated and justified the prosecution, the trial and the detention of those for whom Mrs. Pando exercised her defense – the appropriation of babies, the illegitimate deprivation of liberty, the anti-subversive war, the coup d’état, etc. – and thus also seeks to parody the particular conduct that the demandant adopted for this purpose” (p. 25).

Analysis

The magazine’s headlines allude to many of the acts committed by the armed forces during the last dictatorship in Argentina: the illegitimate appropriation of babies; the detention, torture and disappearance of political leaders and citizens suspected of being left-wing activists (including students, intellectuals, artists, priests and nuns). The strong sexual connotations presented in the text exacerbate the image. Text and image map elements from the different conceptual domains of aggression, pleasure and sex. Through exaggeration, sarcasm, analogies, allusions and double entendres, the magazine harshly criticizes the particular way the group of women chose to capture the attention of the public, by chaining themselves in front of a State building.

A key question in this case is whether this cover should be understood as gender violence perpetrated by the media. According to Argentina’s Comprehensive Protection Law for Women (Law 26.485), passed in 2009, media violence against women takes place when stereotypical messages and images are disseminated that insult, defame, discriminate against or dishonor the dignity of women, by legitimizing unequal treatment or by constructing socio-cultural patterns that reproduce inequality or generate violence against women.

Despite such legal protections, the Court ruled in favor of free expression, by taking into account the specific features of satire and by establishing shared characteristics between caricature and the photomontage. Furthermore, the Court considered the “reading contract” (Verón, 1992) between Barcelona and its readership. According to this idea, the magazine’s readers knew that Barcelona is a satirical magazine, which framed their interpretation of the magazine’s cover and content. As a satirical magazine, Barcelona uses humor, irony, sarcasm and exaggeration to denounce and criticize societal and political issues. By means of figurative and implicit meanings, texts and images are not to be interpreted literally. Barcelona also parodies journalistic conventions, by twisting newspapers’ use of headlines and quotations through photomontages and the use of slang and vulgarity. The magazine mocks institutions, morals and taboos through dark humor and obscene and scatological images.

By acknowledging the special status of Barcelona within the frame of satirical press, the Supreme Court’s final decision set an important precedent regarding the legal status of satirical media in Argentina.

Sources and further reading:

Fraticelli, D. 2008. “La revista Barcelona y el humor local.” LIS Letra. Imagen. Sonido. Ciudad Mediatizada, 2, 117–130.

Gasillón, M. L. 2022. “Revista Barcelona: cuando el humor sarcástico supera la realidad.” Metáfora. Revista de literatura y análisis del discurso, 9, 1–20.

Verón, E. 1992. “Reading is doing: Enunciation in the discourse of the print media.” Marketing Signs, 14/15, 1–12.