Mode of expression: Trademark parody

Publication: T-shirt sold online

Region: South Africa

Relevant dates: 2001 (creation of disputed T-shirt); May 2005 (ruling)

Outcome: Constitutional Court overturns the injunction against Laugh It Off

Judicial body: Constitutional Court of South Africa

Type of law: Civil law

Themes: Parody / Trademark / Brand reputation (tarnishment)

Context

Laugh It Off Promotions v. South African Breweries (Constitutional Court of South Africa, CCT42/04, 27 May 2005) centers on the interaction of trademark law and parody. Laugh It Off Promotions CC is a company that parodies brands by altering the images and words on trademarks and printing them onto T-shirts – both for profit and to engage in social commentary. In this case, T-shirts had been printed with a parody of the well-known Carling Black Label trademark owned by South African Breweries (SAB), which subsequently brought the action.

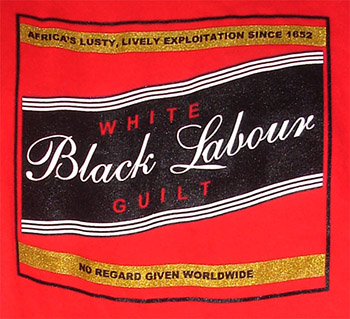

The original trademark consists of two beer labels, respectively reading “America’s lusty, lively beer | Carling Black Label Beer | Brewed in South Africa” and “Carling | Enjoyed by men around the world.” The Laugh It Off parody used the same lettering, color scheme and background as the original, but replaced the wording as follows:

| Original | Parody |

| “America’s lusty, lively beer” | “Africa’s lusty lively exploitation since 1652” |

| “Black Label” | “Black Labour” |

| “Carling Beer” | “White Guilt” |

| “Enjoyed by men around the world” | “No regard given worldwide” |

As ascertained during the proceedings, the message conveyed by the parody T-shirt is that SAB “had exploited and still is exploiting black labour, that it has and should have a feeling of guilt and that SAB worldwide could not care less.”

Legal case

SAB first came to know about the Laugh It Off parody in November 2001. After a series of unsuccessful cease-and-desist letters, SAB filed a lawsuit for trademark infringement. More precisely, SAB accused Laugh It Off of “tarnishment,” that is, harming the reputation of a trademark by associating it with something perverse or deviant. Laugh It Off argued in response that they were simply exercising their freedom of expression, and that famous trademarks – just like any other cultural icon – should not be beyond the reach of public criticism. In their view, the purpose of their parody T-shirts is “to ridicule the marks; to make a statement about the company’s policies or practices; to sound out issues affecting society at large; to assert freedom of expression and, in so doing, to challenge the unconscionable use of trademark laws to silence expressions that are not flattering about the marks.”

In the first round of proceedings, the Cape High Court ruled in favor of the beer company, stating that the message on the shirts was likely to damage the reputation of the marks. Moreover, according to the Court, Laugh It Off could not raise the defense of free expression, as the parody T-shirt was for sale – which means that the popularity of the SAB trademark had been exploited for commercial gain. Lastly, the Court found that the T-shirt was not just a parody ridiculing the Carling trademarks, but rather bordered on hate speech by referring to racial slurs. Therefore, the High Court granted an injunction, ordering Laugh It Off to suspend sale of the T-shirts. This decision was subsequently confirmed by South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal.

Laugh It Off then took the case to the Constitutional Court, which eventually overturned the lower courts’ decision. According to the Constitutional Court, SAB had failed to establish the “likelihood of taking advantage of, or being detrimental to, the distinctive character or repute of the marks.” In other words, there was no evidence that the parody T-shirts could cause any significant commercial harm to the beer company.

Analysis

Remarkably, the Constitutional Court’s decision was solely based on technical grounds in light of the Trademarks Act, as the Court expressly declined to examine whether the satirical or parodic message was protected by freedom of expression. In his concurring opinion, Judge Sachs contended that the judgment should have ruled on the latter question as well and stressed that humorous expression is not only permissible but necessary to the health of constitutional democracy. In Judge Sachs’ words:

If parody does not prickle it does not work. The issue before us, however, is not whether it rubs us up the wrong way or whether Laugh it Off’s provocations were brave or foolhardy, funny or silly. The question we have to consider is whether they were legally and constitutionally permissible. I believe they were eminently so. […] In our consumerist society where branding occupies a prominent space in public culture, one does not have to be a ‘cultural jammer’ to recognise that there is a legitimate place for criticism of a particular trademark, or of the influence of branding in general or of the overzealous use of trademark law to stifle public debate. In such circumstances the medium could well be the message, and the more the trademark itself is both directly the target and the instrument, the more justifiable will its parodic incorporation be.

Laugh It Off’s representative in the proceedings, Justin Bartlett Nurse, explained that their parody technique can be defined as “ideological jujitsu,” where the targeted brand is pitted against its own weight and popularity. This technique can be a powerful tool for social criticism, as illustrated by several other parodies that ended up being litigated in court. For example, in her artwork Simple Living (2007), the Danish artist Nadia Plesner depicted an African child holding a Chihuahua dog and a Louis Vuitton bag. Her intention was to draw attention to the Darfur humanitarian crisis, strategically diverting focus from trivial matters, such as Paris Hilton’s legal issues, which dominated the media at that time. Louis Vuitton subsequently took legal action for design infringement; the case was litigated in the Netherlands, where the artist was residing. In the first round, the District Court of The Hague found in favor of Louis Vuitton. However, this decision was eventually overturned on appeal by the District Court of Amsterdam, which argued that – within the specific circumstances of the case – Plesner’s right to freedom of expression outweighed Louis Vuitton’s property rights, also considering its contribution to public interest debates.

Sources and further reading:

Beck-Watt, Sebastian D. 2017. Just Laugh It Off: Trademark Parody and the Expansion of User Rights. Intellectual Property Journal 30(1), 95-124.

Luypaers, Melissa. 2024. ‘If parody does not prickle it does not work’: Reflections on the Interpretive Challenges of Dark Parody in the Dutch and South African Courts. Open Library of Humanities 10(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.16695