Mode of expression: photograph with edited elements

Publication: magazine

Region: United States, North America

Relevant dates: August 1991 (publication of Vanity Fair cover); early 1994 (publication of parodic poster); 19 February 1998 (outcome)

Outcome: Motion denied (fair use granted)

Judicial body: Appellate Court

Type of law: Intellectual property / Copyright law

Themes: Artistic expression, Parody, Copyright

Context

Picture the actress Demi Moore, seven months pregnant, on the cover of the magazine Vanity Fair in 1991. The renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz had styled the portrait in the manner of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, with Moore in the nude, in profile, with one arm covering her breasts and the other cradling her stomach. The issue became one of Vanity Fair’s all-time bestsellers.

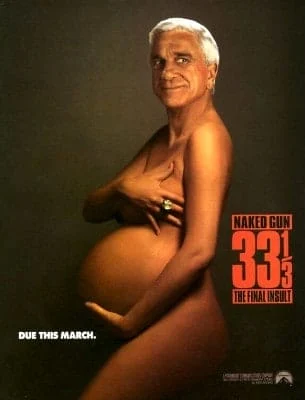

Then, imagine a magazine ad campaign for the forthcoming release of Paramount’s motion picture Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult, which ran in early 1994. The campaign for this slapstick comedy featured a composite of Moore’s body with the face of the actor Leslie Nielsen, the star of the Naked Gun films. The composite was accompanied by a slogan referring to the comedy’s release date: “DUE THIS MARCH.” Notably, the composite did not mechanically copy part of the original Leibovitz photograph; instead, Paramount commissioned another photograph to meticulously resemble the Leibovitz picture while swapping the replacement’s face with Nielsen’s. Attention was paid to mirroring the details of Leibovitz’s photos, including Moore’s posture, skin tone, bodily shape and her large – yet clearly less elegant – ring. In addition, Nielsen does not look serious (as Moore did), but smirks.

Leibovitz protested, arguing copyright infringement. Paramount did not dispute infringement but presented the advertisement as a parody entitled to the fair use defense. Before the appeal court, the central point of disagreement between the parties was the availability of this defense.

Legal Case

The Leibovitz case raises questions from different perspectives, including law and the humanities. This contribution focuses on the case’s legal dimensions, as the court’s finding in favor of fair use elucidates the position of parody under US copyright law.

In U.S. law, fair use enables the use of copyrighted works without rightholder consent for certain purposes and to a reasonable extent. These purposes touch on the exclusive rights that are normally reserved to right holders. First recognized in common law, fair use has since been codified in Section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act. According to the illustrative list of Section 107, potentially permitted purposes include comment and criticism, provided that a weighing of four factors turns out in favor of fair use.

The factors are 1) the purpose and character of the use; 2) the nature of the copyrighted work; 3) the amount and substantiality of the work used; and 4) the effect of the use on the market of the copyrighted work. Below, the scope and interpretation of the factors will be elaborated following their application in the Leibovitz case.

It is worth noting that parody is not explicitly mentioned as a potentially fair use in Section 107, in contrast to European Union copyright law, which contains a specific provision for parody (see our entry on the Deckmyn case, below). Yet, as the Circuit Judges acknowledged, previous cases had confirmed that parody can count at least on some protection under the fair use doctrine on a case-by-case basis. In Leibovitz, the judges indeed found fair use, building on the four-factor test as elaborated by the Supreme Court in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.

Analysis

In doing so, the four factors were weighed as follows.

First, the court reiterated that the purpose and character of the use should be assessed on a spectrum from “‘merely supersed[ing] the objects’ of the original” to adding something new, i.e., a “transformative” use. Therefore, commercial use is not presumptively unfair but should be treated as a separate factor depending on the context. In addition, the parodist must to some extent comment on the original work’s substance or style. Regarding the first factor, the court concluded in Leibovitz that the ad was a transformative work, which “differs in a way that may reasonably be perceived as commenting, through ridicule, on what a viewer might reasonably think is the undue self-importance conveyed by the subject of the Leibovitz photograph.” The court concluded that the “strong parodic nature” of the ad weighed in favor of Paramount, despite promoting a commercial product, as the ad could also be understood as an extension of the film itself.

Second, as the creative nature of the original was found “not [to] provide much help in determining whether a parody of the original is fair use”, the second factor favored the photographer. The court acknowledged, however, that this only had a slight weight in this case.

Third, to determine the amount and substantiality of the work used, the court examined “what else the parodist did besides go to the heart of the original.” That is, on the one hand, the court found that “the degree of copying of protected elements [i.e., artistic elements including lighting, shade and camera angle] was extensive” and even “more […] than minimally necessary.” On the other hand, the court interpreted this factor in light of the first and fourth factors, i.e., the extent to which the “overriding purpose and character” of the ad was “to parody the original” or would “serve as a market substitute for the original,” respectively. Since the 2nd Circuit Court deemed both factors to favor fair use, so too did the third factor, the court found.

Fourth and related, while Leibovitz contended that she missed out on a licensing fee for the use of her work in the ad, the court stressed that no fee was due for the use of a work “that otherwise qualifies for the fair use defense as a parody.” Therefore, since no “market for a derivative work that might be harmed” by the ad was identified, this factor again favored Paramount, also because criticism is a risk artists must endure.

In sum, weighing the four factors, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals found that the balance tilted in favor of fair use. Given the nature of the parodic picture in question, the significance of this fundamental, three-decade old judgment for future cases involving new technologies such as deepfakes will be interesting to follow.

Sources and further reading:

Bazzi, Michael J. & Widdows, Martha J. 1998. Parody and the Fair Use Doctrine Revisited. Entertainment and Sports Lawyer 4(1), 41-64.

Bunker, Matthew. 2007. Advertising and appropriation: Copyright and fair use in advertising. Journal of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A., 54(2-3), 167-182.

Dabo, Miatta Tenneh. 1999. Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp.: Fair Use Doctrine: When Is Copyright Infringement a Parody. University of Baltimore Intellectual Property Law Journal, 7, 155-160.

Lynch, Michael J. 1998. A Theory of Pure Buffoonery: Fair Use and Humor. University of Dayton Law Review 24(1), 1-38.

Patry, William F. The Fair Use Privilege in Copyright Law (Washington D.C.: Bureau of National Affairs, 1995).