Mode of expression: Caricature

Publication: Singlesheet print, etching

Region: London, England (United Kingdom)

Relevant dates: 1803 (publication)

Outcome: Not applicable

Judicial body: not applicable

Type of law: Seditious libel; defamation; copyright; intellectual property

Themes: Satire, parody

Context and Analysis

The late eighteenth century witnessed a flourishing of graphic satire in Britain. Engravers such as James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and Isaac Cruikshank produced a continuous flow of broadsides and prints that were both sharply topical and richly intertextual. Alongside technical innovations—most notably the development of caricature and systems of individualized representation, which facilitated public recognition while complicating legal retribution—visual satirists could draw on a vast repertoire of sources, ranging from the beaux arts to belles-lettres. For those excluded from the Royal Academy, which barred engravers from membership, the realm of ‘high’ art served less as a sanctum of aesthetic reverence than as a convenient trove of imagery ripe for parody. As David Francis Taylor has aptly written, such visual satires, which mined literary works for ripe and pungent allusions, are marked by a “bewildering citational density,” requiring a viewer’s understanding of classical literature, Shakespearean drama, and contemporary fiction.

For visual satirists, literary allusion operated not merely as ornament or referential flair but as a deeply functional device: it structured the political meanings of images, lent them a veneer of cultural legitimacy, and invited elite viewers to interpret caricatures in ways that situated contemporary figures within broader moral, philosophical, or literary frameworks.

Such parodic practices also tested the limits of the law. Though copyright protection was beginning to extend beyond books—most notably with the Engravers’ Act of 1735—visual satire operated in a complex legal grey zone. Engravers were granted rights to their own original works, but not to the ideas or figures they depicted, which could also draw freely on extant literary sources. As Ronan Deazley has observed, the notion that all subjects were fair game—provided no direct copying occurred—reflected a budding concept of the separation between “idea” and “the expression of an idea,” a principle that would become central to modern copyright law. This fragile balance between inspiration and infringement would continue to haunt later iterations of intellectual property jurisprudence, especially as parody gained greater traction as both a form of commentary and a legal defense.

The Engravers’ Act of 1735 (8 Geo. II, c.13), passed after lobbying by the artist and engraver William Hogarth and others, marked a watershed in British copyright law by extending protections to engravings and etchings. Unlike the earlier Statute of Anne (1710), which focused on literary works and book trade regulation, the Engravers’ Act sought to safeguard the creative labor of visual artists from unauthorized reproduction by unscrupulous printsellers and pirate engravers. By conferring exclusive rights for a period of 14 years (later extended and clarified in 1766 and 1777), the law granted engravers the ability to sue for infringement and assert control over the reproduction of their work.

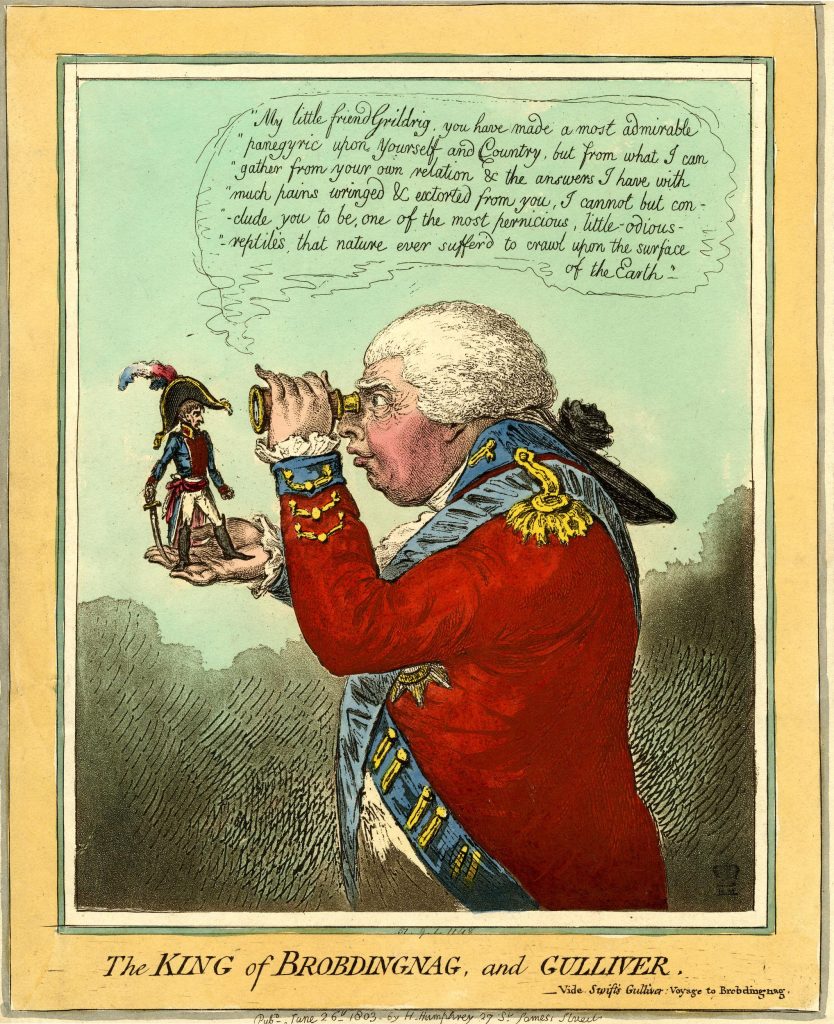

This loose framework permitted satirical artists like James Gillray to draw heavily on the rich cultural archive of literature and drama without fear of legal retribution, even as it introduced questions about authorial originality and creative borrowing that would intensify in the centuries to follow. One of the most iconic examples of literary allusion from this period is Gillray’s The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver (1803). The print, created shortly after the collapse of the Peace of Amiens, depicts King George III holding a diminutive Napoleon Bonaparte in his hand, scrutinizing him through a spyglass. The visual conceit is lifted directly from Gulliver’s Travels (1726), in which the titular character visits Brobdingnag—a land of giants—and provokes the disgust of its king through his defense of European politics.

In Gillray’s adaptation, the allusion is not merely decorative. It provides a framework through which the British monarch’s reaction to Napoleon can be interpreted as moral, rational, and above all, superior. The king’s quoted speech—“My little friend Grildrig…” —is nearly verbatim from Swift’s text, and positions George III as a figure of imperial reason confronting the grotesque vanity of his adversary. Napoleon’s saber and swaggering posture, however, disrupt the fantasy of invulnerability. Though tiny, he is no less dangerous, and the satire subtly acknowledges the growing anxieties around invasion and war.

Gillray’s use of literary parody here operates on several levels: it legitimizes political critique through a culturally familiar text; it allows for caustic satire of contemporary figures under the protective mask of fiction; and it engages the viewer’s cultural literacy in a decoding game that flatters and implicates them. In this regard, the print exemplifies later understandings of parody. For Fredric V. Bogel, for instance, parody is “inescapably imitative,” oscillating between homage and derision. What makes this print particularly notable is how it mobilizes literary allusion to drive home its dual political message: the inferiority of the French tyrant versus the moral superiority of the British monarchy. This is more than mere clever reference, but a deliberate reuse of intellectual content in service of new expression.

Gillray’s print stands at the confluence of several legal and cultural tensions that continue to animate discussions of intellectual property discourse in the 20th and 21st centuries. Today, parody is recognized in many jurisdictions as a form of fair use or fair dealing, exempting it from certain copyright restrictions. Yet legal battles—some which are outlined in the following panels and entries—testify to ongoing uncertainty around the boundaries of permissible appropriation.

Modern courts often look for evidence that a parody is “transformative”—that it adds new expression or meaning to the original—and does not merely substitute for it. By this measure, Gillray’s print would likely be protected under contemporary standards: it recasts Swift’s narrative for pointed political commentary, using visual reinterpretation rather than direct reproduction. Yet the conceptual questions it raises—about authorship, derivative works, cultural capital, and the public domain—remain very much alive. Moreover, the regulatory tension visible in the Engravers’ Act—between safeguarding artists’ rights and allowing cultural dialogue—has only deepened in an era of digital remixing, viral memes, and algorithmic art. The eighteenth-century distinction between copying and originality, idea and expression, has become both more essential and more fragile in light of new technologies that blur these lines.

Sources and further reading:

Bogel, Fredric V. The Difference Satire Makes: Rhetoric and Reading from Jonson to Byron (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001).

Ronan Deazley. (2008) ‘Commentary on the Engravers’ Act (1735)’, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

David Hunter. ‘Copyright Protection for Engravings and Maps in Eighteenth-Century Britain’, Library 6, no. 2 (1987): 128-147.l

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms (London: Methuen, 1985).

David Francis Taylor. The Politics of Parody: A Literary History of Caricature, 1760–1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).