As discussed in the introduction to this section, public figures – and politicians in particular – are usually expected to display a higher level of tolerance to ridicule compared to ordinary, ‘private’ citizens. This principle is well exemplified by several key cases from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) concerning satirical depictions of politicians – from Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria (2007) to Telo de Abreu v. Portugal (2022).

1. Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v. Austria (No. 68354/01, 25 January 2007)

Mode of expression: Satirical painting; photomontage

Publication: Art exhibition

Region: Europe (Austria)

Relevant dates: 3 April 1998 (opening of the exhibition); 5 April 2007 (date of final outcome)

Outcome: ECtHR overturns the fine and injunction against artists’ association

Judicial body: European Court of Human Rights

Type of law: Human Rights Law; Civil Law

Themes: Defamation / Reputation / Satire

Context

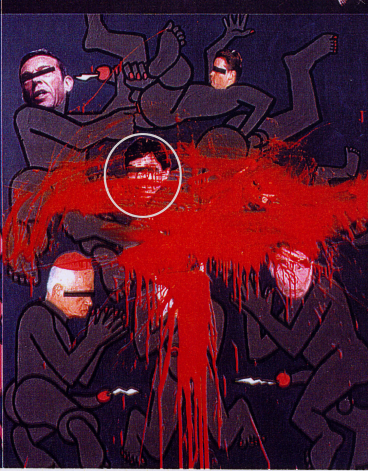

In 1998, an association of Austrian artists called Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Wiener Secession (VBK) sponsored an exhibition, which included among other works the satirical painting “Apocalypse” by the Austrian painter Otto Mühl. The painting featured photomontages showing members of the right-wing conservative Austrian Freedom Party as well as religious figures – such as Mother Theresa and an Austrian cardinal – engaging in graphic sexual acts. One public figure portrayed was Walter Meischberger, an Austrian National Assembly member and a former general secretary of the Austrian Freedom Party. The painting was vandalized during the exhibition, with red paint obscuring much of the offensive part relating to Meischberger.

Legal case

Meischberger sued the artists’ association in the Austrian courts, arguing that the painting debased him and suggested that he indulged in promiscuous sexual activities. The Austrian courts fined the association and issued a permanent injunction against further display of the painting. The case ultimately went to the ECtHR, which found by a divided vote (four judges to three) that the national courts’ decision violated the artists’ freedom of expression, and was neither necessary nor proportionate in a democratic society.

Building on the seminal Handyside v. United Kingdom judgment (1976), the ECtHR observed that freedom of expression should also apply to information or ideas that may “offend, shock or disturb the state or any section of the population.” Moreover, while describing the painting as “somewhat outrageous,” the Court made clear that the painting neither reflected nor suggested reality. Given that the painting used only blown-up newspaper photos of the public figures’ faces (with eyes hidden behind black bars and exaggerated representations of their bodies), the Court concluded that the painting projected only a “caricature of the persons concerned using satirical elements.” From this premise, the Court carefully considered the artists’ right to freedom of expression because “satire is a form of artistic expression and social commentary and, by its inherent features of exaggeration and distortion of reality, naturally aims to provoke and agitate. Accordingly, any interference with an artist’s right to such expression must be examined with particular care.” Ultimately, the ECtHR majority ruled that the permanent injunction was disproportionate and not necessary in a democratic society. The Court also ordered Austria to pay pecuniary damages related to the costs of the domestic judgments as well as other costs and expenses related to the litigation.

Analysis

With its depiction of conservative political figures and members of the Church engaging in obscene sexual acts, Mühl’s painting, like Hustler’s Campari parody discussed above, can be seen as an example of what Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin defined as the “Carnivalesque” – namely a type of expression based on the juxtaposition of the high and the low, or the sacred and the profane. As was the case with the Campari ad in Hustler, carnivalesque profanation does not usually aim to slander specific individuals, but rather to criticize or relativize a given ideology or power structure. From this standpoint, it can be argued that Meischberger is not being targeted as an individual, but as a symbol of a moral order that the artist deemed as artificial or hypocritical.

As the ECtHR’s majority pointed out, the disputed painting belongs to a form of expression that “naturally aims to provoke and agitate.” As a consequence, Mühl’s work should not be judged based on personal taste or subjective feelings of “outrage,” but rather in light of whether it might have unlawfully harmed Meischberger’s human dignity or wellbeing. This latter point was rejected by the Court, as the painting clearly amounted to a caricature (as opposed to a factual defamatory claim) – not to mention the fact that “the part of the painting showing [Meischberger] had been damaged [and] the offensive painting of his body was completely covered by red paint.”

2. Telo de Abreu v. Portugal (No. 42713/15, 7 June 2022)

Mode of expression: Cartoons

Publication: Personal blog

Region: Europe (Portugal)

Relevant dates: September 2008 (reposting of the cartoons); 7 June 2022 (date of final outcome)

Outcome: ECtHR overturns fine against blogger

Judicial body: European Court of Human Rights

Type of law: Human Rights Law; Criminal Law

Themes: Defamation / Reputation / Satire / Gender violence

Context

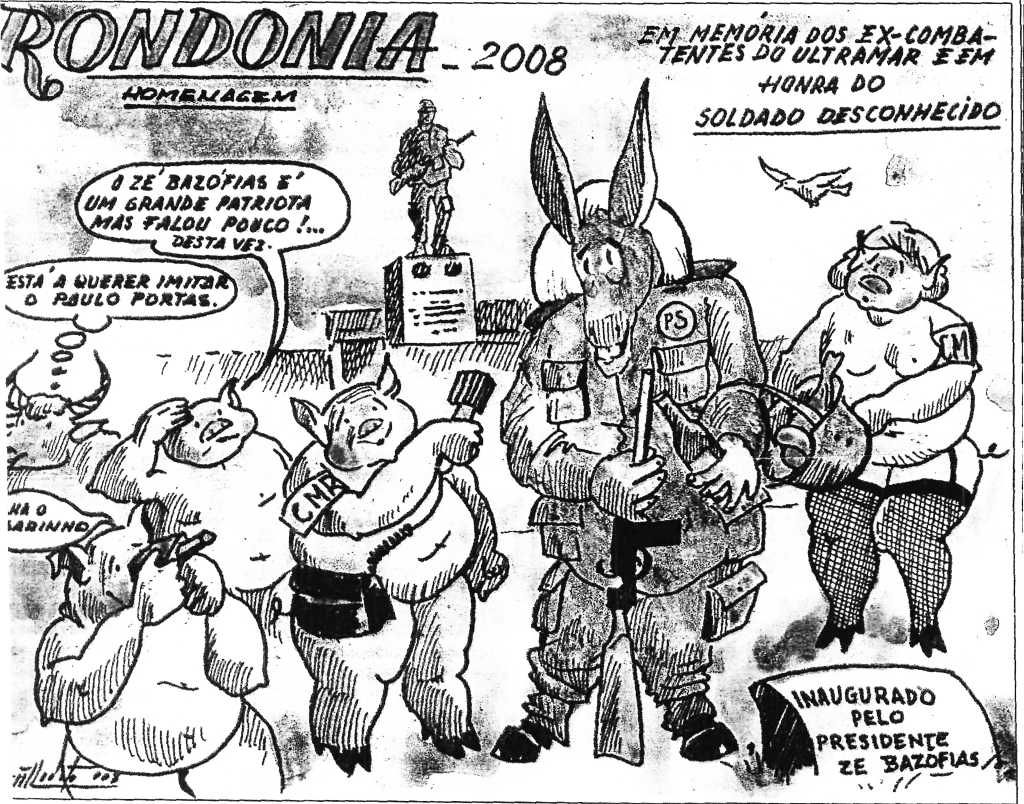

Patricio Monteiro Telo de Abreu is a Portuguese national and former assembly representative in the municipality of Elvas. In 2008, Telo de Abreu reposted on his blog three political cartoons by a local artist, depicting the mayor of Elvas as a donkey, the municipal councilor as a sow wearing sexually suggestive clothing and the rest of the mayor’s political party as “naked” pigs. Next to each post, Telo de Abreu commended the artist’s cleverness.

The cartoons were part of a series published starting in 2007 in the local newspaper O Despertador and entitled “Rondonia” (A Rondónia). This expression was used by a well-known journalist in a political column published in 2006 in the newspaper Público, which made a parodic presentation of the town hall of Elvas – then headed by Mr. José Rondão Almeida, from a political party opposed to that of Telo de Abreu.

Legal case

Soon after the republication of the cartoons, Mrs. E.G. (the municipal councilor depicted in the cartoons) filed a criminal complaint for aggravated defamation against Telo de Abreu and several other defendants before the Elvas Tribunal. She argued that the cartoons posted by Telo de Abreu harmed her reputation by depicting her as a promiscuous woman and by suggesting that she had an intimate relationship with the mayor (who was represented as a donkey in the cartoons).

On 16 May 2009, the Elvas Tribunal convicted Telo de Abreu on aggravated defamation charges (Article 180 §1 of Portugal’s penal code) and ordered him to pay a €1,800 fine and €2,500 in damages jointly with the other defendants. On 26 February 2015, the Evora Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s decision, noting that neither the right to freedom of expression nor personal privacy are absolute. Telo de Abreu then filed an application with the ECtHR, which unanimously established that the domestic courts had violated Telo de Abreu’s freedom of expression. Building on VBK v. Austria and later cases, the Court reiterated that satire is a vital form of democratic expression and that any interference with it should be examined with particular care.

As stressed by the Court, satirical comments on a politician’s personal life must reach a high level of gravity and cause actual professional harm to justify restricting freedom of expression. The ECtHR found that Portugal had failed to demonstrate that this threshold had been met. The ECtHR also argued that the cartoons did not suggest that Mrs. E.G. was engaged in an intimate relationship with the mayor. Instead, the Court claimed, the cartoon should be understood as a broader criticism of the Elvas government and ruling party. The ECtHR also added that harsh punishments, like the one in this case, could deter expression that uses satire to comment on politics or society. The ECtHR therefore reversed the Portuguese courts’ decisions and granted Telo de Abreu €3,466 in material damages and €1,806 in legal fees.

Analysis

While concurring with the ECtHR’s decision, Judges Motoc, Kucsko-Stadlmayer and Schukking wrote separate opinions on the case, highlighting the use of sexist stereotypes in the cartoons against the backdrop of increasing violence against women in politics. In particular, Judge Motoc stressed the importance of recognising the harm caused by what she defined (building on the work of Mona Lena Krook) as “symbolic violence” against women – namely the circulation and reinforcement of disparaging sexist tropes. In this respect, the Judge regretted that the Court’s decision did not take into sufficient account the harmful consequences of gender stereotypes.

However, all concurring judges agreed that the Portuguese courts had unduly violated Telo de Abreu’s freedom of expression, as their decision was based on a decontextualized reading of the cartoons – namely one that neglected the political context in which the “Rondonia” images were published and circulated.

Just like the Pando De Mercado case in Argentina (discussed below), Telo de Abreu raises an important question: How should courts strike a balance between defending free speech on the one hand, and regulating the circulation of harmful stereotypes on the other? Both Argentina’s Supreme Court and the ECtHR took a strong stance in their respective decisions, by placing particular emphasis on the context in which the images were produced and circulated. While the same images might have amounted to unlawful dignitary harm in a different context, both Pando’s photomontage and Telo de Abreu’s cartoons could understandably be seen as lawful (if distasteful) instances of political satire.

Sources and further reading:

Alkiviadou, Natalie. 2022. Ain’t that funny? A jurisprudential analysis of humour in Europe and the U.S. The European Journal of Humour Research 10(1). 50–61. https://doi.org/10.7592/ejhr.2022.10.1.649

Balzaretti, Sofia. 2022. Political Satire and Sexist Stereotypes: A Critical Insight on the Case of Patrício Monteiro Telo de Abreu v. Portugal. Strasbourg Observers, 14 September. URL: https://strasbourgobservers.com/2022/09/14/political-satire-and-sexist-stereotypes-a-critical-insight-on-the-case-of-patricio-monteiro-telo-de-abreu-v-portugal/

Godioli, Alberto and Young, Jennifer. 2023. Humor and Free Speech: A Comparative Analysis of Global Case Law. Columbia Global Freedom of Expression, Special Collection. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8105760