Dr Alberto Godioli (University of Groningen)

How many of you still remember Cocaine Bear, the outlandish B-movie which acquired viral internet fame in early 2023? For those who do, a certain sense of déjà vu might have been evoked by the recent lawsuit concerning another white-powder-snorting ursid – namely a parody version of the beloved Paddington Bear, which first appeared in Michael Bond’s children’s book A Bear Called Paddington (1958) and has enjoyed countless TV and cinema adaptations since then. The unhinged, drug-ingesting Paddington alter ego stars as the the host of The Rest is Bulls*!t – a YouTube show by the British satirical franchise Spitting Image, well-known for its foul-mouthed puppet caricatures of celebrities and politicians (including, in this case, show co-host Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex).

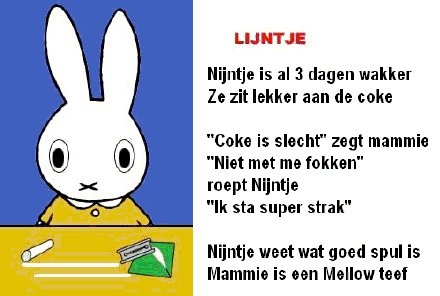

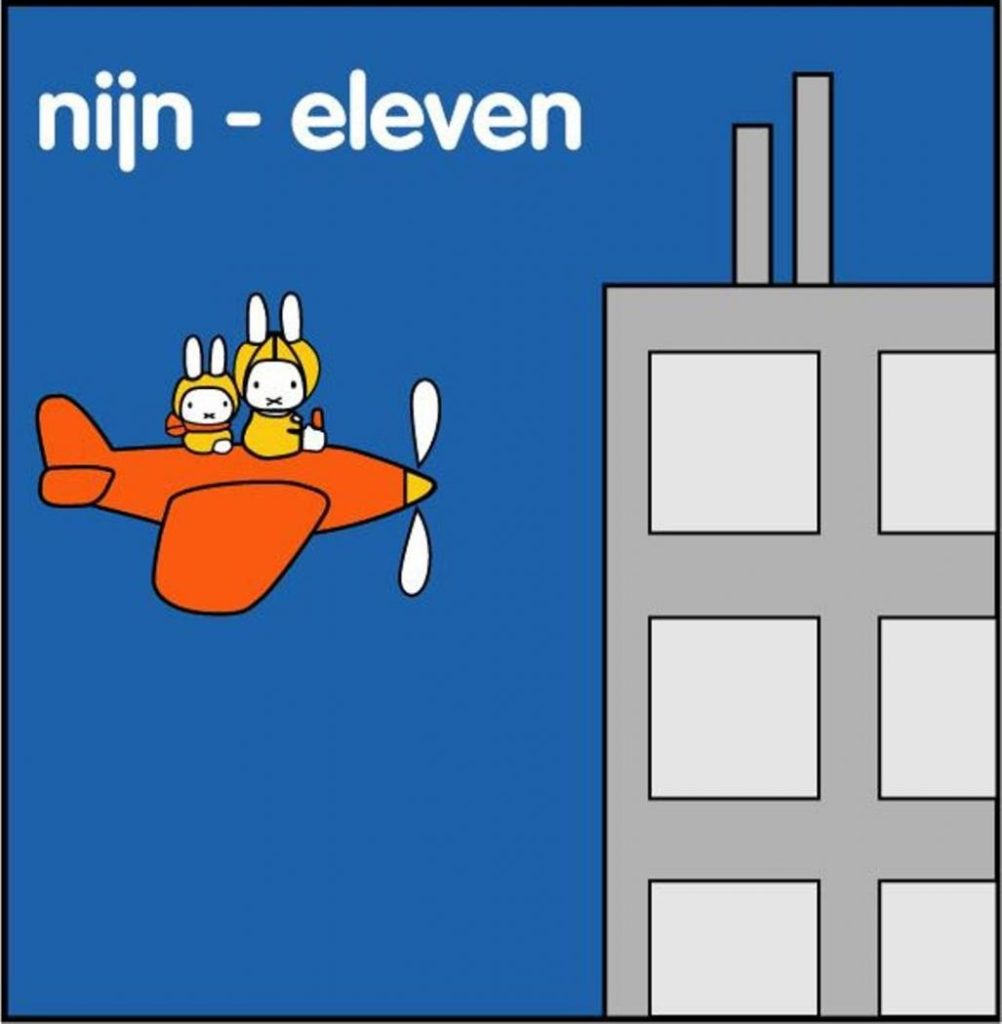

The Rest is Bulls*!t was launched in July 2025. Only a few days ago, however, it was announced that the producers of the Paddington films and Michael Bond’s estate filed a High Court complaint against Avalon (the company behind Spitting Image), citing copyright and design rights concerns. While the details of the lawsuit are still unclear, our sense of déjà vu also brings us back to previous Intellectual Property cases, involving unsavoury depictions of popular characters from children’s books or TV shows.The closest precedent to the Paddington controversy is probably the Dutch case Mercis c.s. v. Punt.nl (2011), focusing on seven parodic images of Nijntje or Miffy – a well-beloved fictional rabbit appearing in a series of picture books, drawn and written by Dutch artist Dick Bruna. Among other things, the images portrayed Miffy under the influence of pills, preparing a line of cocaine, and driving an airplane into the Twin Towers – the latter two examples being based on puns with the name Nijntje, the word ‘lijntje’ (little line) and the date ‘nijn [pronounced nine] eleven’.

The actions were brought by Mercis (the company holding copyright and trademark rights to Miffy) and creator Dick Bruna. Both argued that the web hosting company Punt.nl violated their copyright and trademark rights, by facilitating the online publication of the disputed images. Mercis and Bruna filed a motion to take down the images, as well as to prevent Punt.nl from allowing their websites to publish any images with the likeness of Miffy under the Dutch Copyright Act and the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property (Art. 2.20 par. 1c and 2.20 par. 1d BCIP). In the first instance ruling, the Amsterdam District Court allowed the reproduction of five of the seven images, under the parody exception of Art. 18b Copyright Act. However, it held that the two remaining images (namely the ‘Pilletje’ and ‘Nijn-Eleven’ parodies above) were in violation of Art. 2.20 par. 1d of the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property, as they did not keep sufficient “distance” from the figurative marks registered by Mercis. That is, in those two images, the visual and stylistic features employed in the take-off were found to be too similar to the original Miffy, in order to fully qualify as a parody.

Mercis and Bruna subsequently appealed against the first instance court’s decision to allow the online publication of five out of seven images. In turn, Punt.nl also filed a cross-appeal. Bruna specifically invoked the droit au respect (right to respect) for his work, as referred to in Art. 25, par. 1d, of the AW. Moreover, the appellants stressed the risk of confusion for young children, adding (in Bruna’s words): “Miffy belongs to the children, you must leave her alone” (quoted at 4.16). In September 2011, however, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal concluded that all seven images actually qualified for the parody exception. In the appellate court’s view, the two remaining images – just like the other five – maintained “the recognizability of the original necessary for a parody”, while also taking “sufficient distance from the original not to qualify the parody as a mere copy” (at 4.13). In the balancing act between Intellectual Property rights and freedom of expression, the court emphasised the importance of protecting expression in the form of parody.

The relevance of this principle is all the more evident when the parody is created in the context of political satire, or otherwise seeks to comment on broader social issues. A telling example from the United States is Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., indicating the 11 claims brought by Mattel against MCA Records over the 1997 hit song ‘Barbie Girl’ by Danish-Norwegian group Aqua. In the song, singer Lene Nystrøm famously impersonates Barbie in a high-pitched voice, uttering lines such as “You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere” and “I’m a blonde bimbo girl, in a fantasy world / Dress me up, make it tight, I’m your dolly”. Amongst other claims, Mattel argued that the song violated Barbie’s copyrights and trademarks, and that its lyrics tarnished the reputation of the brand.

After the Central District of California ruled in favour of MCA, Mattel appealed against the decision. However, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the first instance ruling, reiterating that the song qualified as a protected parody under trademark law and First Amendment rights. In the court’s view, the word ‘Barbie’ has become such an integral part of public discourse, that it transcends the identifying purpose of the trademark: “Trademarks often fill in gaps in our vocabulary and add a contemporary flavor to our expressions. Once imbued with such expressive value, the trademark becomes a word in our language and assumes a role outside the bounds of trademark law” (at III.A). In other words, the parody song used Barbie as a shortcut to criticise “the values that Aqua contends she represents” (at III.B) – such as, arguably, consumerism or the objectification of women.

Comparably to Barbie, Paddington has acquired an iconic status in public discourse, albeit in ways that are quite different from Mattel’s doll. In particular, Bond’s creation has established itself as a signifier for a whole set of self-perceived ‘British values’. As stated by Rosie Alison, one of the producers behind some of Paddington’s screen adaptations, in a 2024 interview: Q: “Often, when we talk about Paddington, we say that he upholds very British values. Is that a fair comment?” A: “It’s how we like to think of ourselves, isn’t it? He represents tolerance and inclusiveness and compassion and kindness and generosity. That’s what we want to feel”. Inclusiveness is indeed often seen as a key aspect in the story of Paddington – who, as narrated in Bond’s first book, left “darkest Peru” to embrace prototypically British habits and manners. At the same time, the ideological assumptions behind this narrative may well be subject to criticism:

In Paddington’s enthusiastic adoption of British values, he arguably embodies the “good immigrant” archetype; the kind of respectful and compliant model minority that even the most die-hard UKIPer would find acceptable. Not all migrants speak fluent English in a plummy accent, nor have they spent their lives obsessing over British culture, nor do they readily discard their real name because it’s too difficult for English people to understand. If Paddington is an immigrant icon, he’s an assimilationist one. For right-wing conservatives, there’s plenty to like, not least the way the character embodies certain traditional British social norms such as politeness and good manners. In the films, Paddington’s otherness derives in part from the way he harks back to an idealised pre-war mode of Britishness: rather than being ‘foreign’, he is effectively more British than the rest of us. (Greig 2022; see also Smith 2020)

Does the Spitting Image parody aim to ridicule (among other things) the particular view on Britishness that Paddington is deemed to symbolise, including its assimilationist undertones? This seems plausible, also considering the puppet’s first line in the YouTube show, as he switches from spotless Queen’s English to his ‘authentic’ Latin-American accent: “I don’t really talk like Ben Winshaw [the English actor voicing Paddington in the 2014 film]. No, I am from Peru, motherf*ckers”. Either way, it is easy to imagine how prohibiting unpleasant parodies of children’s characters who have reached the status of cultural icons (from Barbie to Paddington) can have a chilling effect on satirical expression addressing public interest issues.

Of course, despite the good precedents set by the Nijntje and Barbie decisions, not all cases result in a happy ending for parody. In May 2018, the Belgian delegation of Greenpeace launched a campaign featuring Maya the Bee in a parody video advertisement. The video presented Maya the Bee promoting “children’s cigarettes” – which was meant by Greenpeace as a way to satirize how Studio 100 (the company holding copyright and trademark rights in the Benelux area) had recently launched processed meat products using Maya’s image. In the ensuing lawsuit, Studio 100 claimed that Greenpeace was using Maya the Bee without its authorisation, violating its rights to exploit the character commercially. Moreover, the estate of Maya’s creator, Waldemar Bonsels, argued that Maya’s reputation, character, and the author’s rights to integrity were compromised by the association of the character with harmful products (i.e., cigarettes). Greenpeace, on the other hand, maintained that the campaign should be protected by the parody exception under European copyright law.

In April 2019, the Commercial Court of Brussels ruled that, although the campaign did meet some of the legal criteria for a parody, it had a disproportionate impact on the rights and reputation of Studio 100 and the moral rights holder. In particular, in the court’s view, the widespread circulation of the campaign made it likely for children to see it, and thereby associate Maya with smoking – which risked harming the reputation of the character and its “child-friendly” character. The court also stressed that Greenpeace had used the images of Maya the Bee in an unmodified form, which could create an impression that Studio 100 itself produced the cigarettes advertisement. Nevertheless, as highlighted by commentators, “the Brussels Court’s reasoning can be criticised for its failure to proportionately balance the free speech rights with the protection of copyright, as well as for (mis)using the copyright’s mechanisms of the moral rights protection in order to reach, essentially, the goal of securing the reputation of a commercial enterprise” (Geiger and Izyumenko 2023, p. 14; see also Voorhoof 2019).

As suggested by these mixed precedents, it is hard to predict how the Paddington case will play out – especially at this early stage, in which the details of the rights holders’ claims are still unknown. However, one thing bears repeating: popular fictional characters, including those from children’s books or toys, play a vital role in the collective imagination, often becoming shortcuts or symbols for a whole system of values. Restricting their parodic use inevitably comes at a cost for freedom of expression, and cannot really stop those characters from fulfilling their destiny – namely living an adventurous life in the realm of public discourse, beyond the storyworlds devised by their original creators. As Paddington would put it, “things are always happening to me. I’m that sort of bear”.